Walter Pater: Continuity and Discontinuity. International Walter Pater Conference

Lieu : Paris, Maison de la recherche (Serpente)

International Walter Pater Conference

3 -5 July 2014 Maison de la Recherche (Serpente), Paris Sorbonne University

Walter Pater: Continuity and Discontinuity

See also the VALE Website (Paris-Sorbonne)

Keynote speakers

Laurel Brake (Birbeck, University of London)

Lene Østermark-Johansen (University of Copenhagen)

Thursday 3, Friday 4 and Saturday 5 July 2014

Conference organizers:

Bénédicte Coste, University of Burgundy – TIL

Anne-Florence Gillard-Estrada, University of Rouen – ERIAC

Martine Lambert-Charbonnier, Paris-Sorbonne University – VALE

Charlotte Ribeyrol, Paris-Sorbonne University – VALE

Maison de la Recherche

28, rue Serpente

75006 Paris

Tel : 33 (0)1 53 10 57 00

Metro : Odéon, Saint-Michel

Website

We are grateful for the support of the Walter Pater International Society.

The conference will host a meeting of the contributors and subscribers to the Pater Newsletter, published by the Pater Society.

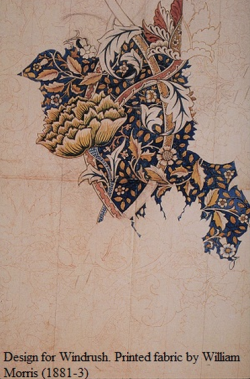

Design for Windrush printed fabric by William Morris, 1881-83 (Identification from Linda Parry, ed.: William Morris, Abrams, 1996, ISBN 0-8109-4282-8, p. 265).

Source: Planet Art CD of royalty-free PD images William Morris: Selected Works (see online)

Call for Papers: “Walter Pater: Continuity and Discontinuity”

As carefully elaborated in The Renaissance, history and art history are made up of continuities and discontinuities between epochs, artistic forms, artists and thinkers. Pater termed “renaissance(s)” the ruptures and revivals masked by the apparent seamlessness of temporality. The Renaissance was indeed an unceasing return to the “standard of taste” set in Antiquity, an acknowledgment of its permanence in men’s minds and acts. However, it was also a discovery of “New experiences, new subjects of poetry, new forms of art” (“Two Early French Stories”) that called into question the conditions of life and art. These “exquisite pauses in time” were Pater’s most effective means of linking the continuous and discontinuous. In his other writings, whether published or fragmentary, Pater continued to envisage and apply such patterns to study Europe’s intellectual and cultural traditions. In keeping with this complex patterning, the 2014 Paris International Conference will explore Continuity and Discontinuity in Pater’s writings from an interdisciplinary perspective, reflecting his diverse engagements with literature, the arts, history and philosophy. We invite proposals that examine Continuity/Discontinuity with reference to all aspects of Pater’s work, including but not limited to:

– Themes and images (representations of violence, cycles and myths of death and rebirth…)

– Generic, formal and stylistic features

– Different types of publication (book form, periodicals…)

– Pater’s reading of other writers from the classics to his contemporaries (intertextuality, the text as a palimpsest, quotations and misquotations, interpretation and misinterpretation…)

– Response to existing fields of research (anthropology, archaeology, art history, literary criticism…)

– Pater’s understanding of the visual arts

– The critical reception of Pater’s writings; his biography. Are there different Paters?

We are grateful for the support of the Walter Pater International Society.

Presentations and papers will be delivered in English.

Design for Windrush printed fabric by William Morris, 1881-83 (Identification from Linda Parry, ed.: William Morris, Abrams, 1996, ISBN 0-8109-4282-8, p. 265).

Source: Planet Art CD of royalty-free PD images William Morris: Selected Works (see online)

International Walter Pater Conference

“Walter Pater: Continuity and Discontinuity”

3 -5 July 2014

Maison de la Recherche

28, rue Serpente 75006 Paris

Organisation:

Bénédicte Coste, University of Burgundy – TIL

Anne-Florence Gillard-Estrada, University of Rouen – ERIAC

Martine Lambert-Charbonnier, Paris-Sorbonne University – VALE

Charlotte Ribeyrol, Paris-Sorbonne University – VALE

Keynote speakers:

Laurel Brake (Birbeck, University of London)

Lene Østermark-Johansen (University of Copenhagen)

PROGRAMME

Thursday 3 July

9.00-9.30 Welcome by Pascal Aquien, Vice-President of the Scientific Council of Paris-Sorbonne University

9.30-10.30 Session 1: Pater in and out of his texts

Chair: Laurel Brake (Birbeck, University of London)

Lesley Higgins (York University, Canada) and David Latham (York University): “The Later Pater: The Choice of Copy-Text for The Collected Works of Walter Pater”

Joseph Bristow (University of California, Los Angeles): “‘What an interesting period… is this we are in!’: Walter Pater and the Synchronization of the ‘Aesthetic Life’”

10.30-11.00 Coffee break

11.00-12.30 Session 2 Pater in and out of his texts

Chair: Lene Østermark-Johansen (University of Copenhagen)

Stefano Evangelista (Trinity College, University of Oxford): “Walter Pater’s Love of Letters”

Kenneth Daley (Columbia College, Chicago): “The Problem of ‘Feuillet’s La Morte’”

Robert M. Seiler (University of Calgary, Canada): “The Book as Aesthetic Object”

12.30-14.00 Lunch Break : free lunch in town

14.00-15.30 Session 3 Dis/continuous Art Criticism

Chair: Barrie Bullen (Royal Holloway College)

Pascal Aquien (Paris-Sorbonne University): “A Reading of the Mona Lisa”

Elizabeth Prettejohn (University of York, UK): “Pater and Sculpture: Between Ancient and Modern”

Anne-Florence Gillard-Estrada (University of Rouen): “Walter Pater and Contemporary Art Critics: Dis/Continuities”

15.30-16.00 Coffee Break

16.00-17.00 Session 4 Political masculinities

Chair: David Latham (York University)

Michael Davis (Le Moyne College): “Castration, Incorporation and Queer historiography in ‘Notes on Leonardo da Vinci’”

Noriyuki Nozue (Osaka City University): “Pater’s Political Playing with Englishness in ‘Emerald Uthwart’”

17.00-18.00 Keynote Speaker: Lene Østermark-Johansen (University of Copenhagen): “’What came of him?’ Change and Continuity in Pater’s Portraits »

Chair: Charlotte Ribeyrol (Paris-Sorbonne University)

18.00-19.30 Cocktail at the Maison de la Recherche, Serpente

Friday 4 July

09.30-10.30 Session 5 Life and (after)lives of Pater

Chair: Frédéric Regard (Paris-Sorbonne University)

Martine Lambert-Charbonnier (Paris-Sorbonne University): “Discontinuity in biography: are there different Paters?”

Elisa Bizotto (IUAV University of Venice): “Dis-continuous Minds: Madness in Pater and After”

10.30-11.00 Coffee Break

11.00-12.30 Session 6 Pater’s New Sensations

Chair: Catherine Delyfer (University of Toulouse II-Le Mirail)

Rachel Teukolsky (Vanderbilt University, USA): “Walter Pater and Sensation”

Catherine Maxwell (Queen Mary, University of London): “Air and Atmosphere in Walter Pater”

Nicholas Manning (Paris-Sorbonne University): “Unimpassioned Passion: Inner Excess and Exterior Restraint in Pater’s Rhetoric of Affect”

12.30-14.00 Lunch Break

14.00-15.00 Session 7 Writing Lives: Self and Other

Chair: Carolyn Williams (Rutgers University, USA)

Kit Andrews (Western Oregon University, USA): “Walter Pater’s Lives of Philosophers: the Discontinuities of Life and Thought”

Ulrike Stamm (Humboldt-Universität, Berlin): “Pater and the Dis/continuities of Cultural Alterity”

15.00-15.30 Coffee Break

16.00-17.00 Keynote Speaker: Laurel Brake (Birbeck, University of London): Pater and the new media: the ‘child’ in the ‘house’

Chair: Martine Lambert-Charbonnier (Paris-Sorbonne University)

Visit of the Louvre in the evening for the participants

Saturday 5 July

9.30-11.00 Session 8 Intertextuality as discontinuity

Chair: Stefano Evangelista (Trinity College, University of Oxford)

Carolyn Williams (Rutgers University, USA): “Textual Time Zones”

Thomas Albrecht (Tulane University, New Orleans): “Cosmopolitanism in ‘Joachim du Bellay’”

Daichi Ishikawa (Keio University, Tokyo): “A Great Chain of Curiosity: Pater’s ‘Sir Thomas Browne’ and its Nineteenth-Century British Context”

11.00-11.30 Coffee Break

11.30-13.00 Session 9 Going foreign: Pater abroad

Chair: Kenneth Daley (Columbia College, Chicago)

Bénédicte Coste (University of Burgundy): “Walter Pater: French Continuity and Discontinuity”

Jonah Siegel (Rutgers University, USA): “Pater’s Houses: The Afterlives of an Image”

Sylvie Arlaud (Paris-Sorbonne University): “Walter Pater’s reception in fin-de-siècle Vienna”

13.00-14.00 Lunch Break: free lunch in town

14.00-15.30 Session 10 Pater and 19th-century beliefs

Chair: Claire Masurel-Murray (Paris-Sorbonne University)

Adam Lee (Sheridan College): “Trace, Race, And Grace: The Influence of Ernest Renan’s Souvenirs d’enfance et de jeunesse on Pater’s Gaston De Latour”

Sarah Lyons (University of Kent): “Only the Thorough Sceptic Can be the Perfect Saint: Altruism, Agnosticism and Pater’s Marius the Epicurean”

Dominique Millet-Gérard (Paris-Sorbonne University): “Walter Pater: Beauty as a ‘poetic principle’ of continuity”

15.30-16.00 Coffee Break

16.00-17.30 Session 11 New Pater Criticism

Chair: Lesley Higgins (York University, Canada)

Dennis Denisoff (Ryerson University, Canada): “’One continuous shelter’: Pagan Ecology in Marius the Epicurean”

Megan Becker-Leckrone (University of Nevada): “Walter Pater in the Wilderness”

Amanda Paxton (York University, Canada): “The Theory of the Moment in a Comparative Perspective: Coleridge, Pater, and Bergson”

17.30-18.00 Meeting of the Pater Newsletter’s contributors and subscribers

19.00 Conference dinner, Restaurant Bouillon Racine

Design for Windrush printed fabric by William Morris, 1881-83 (Identification from Linda Parry, ed.: William Morris, Abrams, 1996, ISBN 0-8109-4282-8, p. 265).

Source: Planet Art CD of royalty-free PD images William Morris: Selected Works (see online)

Thomas Albrecht (Tulane University): “The Cosmopolitanism of Joachim du Bellay”

This paper engages in the current critical debate among Pater scholars about the usefulness and appropriateness of the term cosmopolitanism for understanding Pater’s writings. It specifically contributes to this debate by considering whether the ethical dimension of Pater’s aesthetics can be defined as a form of cosmopolitanism. The focus of the paper is on Pater’s essay about the sixteenth-century French poet and critic Joachim du Bellay in The Renaissance. It may seem counterintuitive to engage with the question of Pater’s cosmopolitanism via an essay about a writer whose characteristic “virtue” Pater defines in terms of nativism: an intense appreciation of the beauty and power of a native place, of a living vernacular French language, and of a localized natural world. Yet the paper makes the case that the du Bellay essay is relevant to any consideration of the relationship between cosmopolitanism and Pater’s writings. Pater’s account of du Bellay’s sojourn in Rome is particularly helpful in this regard, imagining du Bellay as a modern, Baudelaire-like sensibility wandering aimlessly amidst the fragmentary ruins of the ancient city, filled with ennui and producing poems Pater suggestively calls “pale flowers.” But the paper not only examines the extent to which Pater defines du Bellay (and by extension himself) in terms of a modern cultural cosmopolitanism. It also asks whether Pater’s essay and The Renaissance more generally can be defined in terms of cosmopolitanism in the philosophical, ethical sense of an unconditional responsibility. It thereby attempts to pinpoint an elusive ethical strand in The Renaissance, a strand to which Pater alludes in the “Conclusion,” and which as per his suggestion there he makes more explicit in Marius the Epicurean.

Kit Andrews, Western Oregon University: “Walter Pater’s Lives of Philosophers: the Discontinuities of Life and Thought”

Pater’s biographical writings (historical and imaginary) may most often depict lives of artists and writers, but Pater’s lives of philosophers constitute a curiously persistent thread throughout his oeuvre. In his essays and short stories, this thread brings together his treatments of Pico della Mirandola in The Renaissance, the Spinozist Sebastian van Storck in Imaginary Portraits, and the Kantian Samuel Taylor Coleridge in Appreciations (whose “singular intellectual happiness” Pater found in his “inborn taste for transcendental philosophy”). In his more extended works, this relation between the sensations of an individual’s experience and the ideas of systematic philosophy plays itself out through Marcus Aurelius in Marius the Epicurean, as it does through Montaigne in Gaston de la Tour. To some extent the culminating articulation of Pater’s ongoing investigation may be his most explicit and most developed philosophical work Plato and Platonism. But even after radically resituating Plato’s idealism within the twin gravitational forces of the lives of Socrates and Plato, Pater restaged this forcefield once again in the essay on Pascal he was working on at his death. A prominent aspect of this Paterian biographical-philosophical sub-genre is the effort to overcome the distance between the variegations of life and the structures of thought. As early as his 1868 review of William Morris’s poetry, Pater warns against the pitfalls of “acquiescing in a facile orthodoxy, of Comte, or of Hegel, or of our own.” Twenty-five years later in Plato and Platonism (1893), he champions what he claims as an alternative, more inclusive, type of philosophy: the essayistic philosophical form of Plato’s dialogues with their “essentially informal . . . un-methodical, method.” Though fascinated with the potential of essayistic philosophy to bridge the gap between life and thought, Pater also remained preoccupied with the peculiar forms this distance may assume in the tensions between the lives philosophers led and the philosophies they constructed. Through considering Pater’s lives of philosophers as a continuous thread in his works, this paper will trace his efforts to recover a continuity from the discontinuities of life and thought.

Sylvie Arlaud, University Paris Sorbonne: “Walter Pater’s reception in fin de siècle Vienna”

In November 1894 the young Austrian poet Hugo von Hofmannsthal published an essay about the life and works of Walter Pater in Die Zeit. Pater would from then on grow to be, alongside with Swinburne, Ruskin, Arnold and Wilde, a key figure in Hofmannsthal’s reflections about criticism as a way to lead out of a form of art which seems incapable to relate to the past in a creative way. In his essay, Hofmannsthal focuses on three representative works of Pater, seen as a mirror of Young Vienna. The Renaissance and Imaginary Portraits allow him to reinstate imagination as a major critical and historical tool and to show a new way to apprehend the place of the subject in the critical process. Marius the Epicurean can be read as the failure of all the promises Hofmannsthal saw in the first two books. Each book was a source of inspiration for the young poet; Hofmannsthal tried his own imaginary portrait in his famous imaginary letter from 1902, and his reservations about Marius the Epicurean found their way into the secluded world of beauty in the Tale from 672th night (1895). The present contribution would like to put Hofmannsthal’s reception of Pater in a wider context and see how, shortly after his death, his essay shaped a Viennese Pater who might not be consistent with the French or the British Pater of the same period. It will therefore be necessary to consider other intermediaries, like Stefan George, Rudolf Kassner, Karl Kraus or Leopold von Andrian, as well as the translators and publishers who contributed to Pater’s reception in order to verify the coherence of this reception pattern.

Megan Becker-Leckrone, University of Nevada: “Walter Pater in the Wilderness”

As a specialist in the history of critical theory and a scholar of late-nineteenth-century literature, with an emphasis on Pater’s aestheticism, I am intrigued by Pater’s role—his afterlife, so to speak—In ushering in the formalist and New Critical theory that dominated criticism for perhaps half of the twentieth century. It’s easy to track the re-emergence of Pater as a figure of study for literary critics of differing persuasions, but harder to trace his role among literary critics, as himself part of the history of literary critical theory. I borrow my title from Geoffrey Hartman’s Criticism in the Wilderness: The Study of Literature Today (1980), where he examines just the period of time I hope to sketch in my own paper; namely, from Pater’s death to Hartman’s present (in this book) to our own. I am interested, specifically, in the dialectical, pendular, shifts from aesthetic or impressionist criticism to the formalism or supposed objectivism, arguably spearheaded by the profoundly influential pronouncements of T. S. Eliot, of the Anglo-American New Criticism. Hartman’s general claim is that Eliot generated a “gulf between philosophic criticism and practical criticism” by “rag[ing] finely against the dissociation of sensibility from thought,” of “intellect from emotion” (4) that set up the conditions for a new sense that the task of the critic was, could be, and should be “objective,” a discipline in itself, distinct from the stew of philosophy, art criticism, subjective expression Pater’s work retrospectively came to represent.

Elisa Bizzotto, IUAV University of Venice: “Dis-continuous Minds: Madness in Pater and After”

The theme of madness is pervasive in Pater’s fiction and recurs in his criticism. According to Robert Keefe, who devoted special attention to it, Pater’s perception of the subject was pioneering, since the “Conclusion” to The Renaissance made the English aware “of the discontinuities of the self” before the advent of Charcot, Janet and Freud. His views can thus be interpreted in terms of breaking with prior notions and, on the other hand, envisioning of new ideas that particularly affected the representations of madness in British literature of the 1890s. As in Pater, these representations were set in historical periods of cultural transformation—often the late Middle Ages or the contemporary late-Victorian era—in which radical disruptions occur despite the disturbing permanence of the past.

Pater’s seminal interest in madness was possibly enhanced by his brother’s job as a psychiatrist in an asylum for the insane. Although quite detached from the rest of the family, William Pater was brought closer to them by his final illness, offering the writer the opportunity to gain first-hand experience in the field of mental maladies. Posthumous thoughts on William, “who quitted a useful and happy life” in April 1887, as stated in Appreciations, might have led Pater to reconsider issues that had always fascinated him. His later fiction actually explores the theme of madness from even newer perspectives, frequently insisting on its contiguity with art and religion. These approaches were subsequently shared by Oscar Wilde, Arthur Symons, Ernest Dowson, Vernon Lee and Eugene Lee-Hamilton, whose fictional characters—mostly authorial projections—tend to manifest mental disorder through artistic expressions, fervent mysticism or asceticism. By establishing a rupture with previous images of madness, Pater initiated a continuum with aestheticist and decadent literature on the topic at thematic, rhetorical and symbolic levels. His influence could still be detected in Modernism.

Laurel Brake, Birbeck, University of London: “Pater and the new media: the ‘child’ in the ‘house’”

In this lecture, I will explore how Walter Pater’s writing career, and the trajectory, locations and character of his publications relate to the media of his day. Pater’s writing career exactly maps onto the timeline and development of the new media of the 1860s, right through until the mid 1890s. In this sense he is a ‘child’ in the ‘house’ of publishing. What I mean by new media in the 19th century are the new forms of the newspaper, magazine and review genres that follow the repeal of the newspaper taxes 1855-61, in which I shall argue Walter Pater’s writing almost exclusively appeared. How did Pater navigate the shoals of the new journalism, the movement between lectures, periodical article and book publication, and celebrity in comparison with peers, such as J. A. Symonds, and his juniors, such as Arthur Symons and Oscar Wilde? I will also investigate serials to which he was invited to contribute but did not (eg the Century Guild Hobby Horse, Good Words, the Illustrated London News and the Yellow Book) to explore the limits of his participation in the new journalism, and the avant garde as well as the popular press. Lastly, I will ruminate on the position of ‘Pater’ and the new media in the 21th century, and in the forthcoming edition.

Joseph Bristow, University of California, Los Angeles: “’What an interesting period . . . is this we are in!’: Walter Pater and the Synchronization of the ‘Aesthetic Life’”

Walter Pater’s unpublished fragment, “The Aesthetic Life” (c. 1893), amounts to his boldest attempt to imagine the possibility that a discerning male subject might thrive in the sordid world of urban modernity. For Pater, this prospect is especially urgent in a late nineteenth-century intellectual culture that has sadly capitulated to two deadening beliefs in the “unchangeable”: on the one hand, the fact-based demands of modern scientific rationalism, which proceeds “from point to point within the sensuous boundary,” and on the other hand, the persistence of outmoded forms of spirituality, which assert the truth of “unseen realities” that are “wholly correspondent to man’s aspirations.” Gone, in Pater’s view, is “the magnificent free thought of creation.” In particular, “creative energy” and the “imagination” appear to have little room in a present universe tethered to the dismaying study of suffering, whether in the shape of scientific inquiries into an “incurable disease” or in the religious “master” figure of Lazarus, miraculously raised from the dead at Christ’s command. In Pater’s view, the only pleasures that such bleak philosophies will tolerate are those of others. In no respect do these forms of science and religion capture “the unsophisticated presentations of eye and ear,” the lively and enjoyable responsiveness of the human subject to the “cheerfully lit world of sense.” This summary of Pater’s unfinished essay draws into focus the problems that sometimes emerge in his aesthetic historicism—which frequently strives to find a subject whose evolved sense-perceptions might synchronize with the amassing and “heterogeneous” layers of culture that lurk beneath the surface of an otherwise ugly modernity. The purpose of this essay is clearly ensure that this ideal male subject, whose presence already in principle exists, can enjoy an almost Darwinian “fit” with a cultural heritage that is richer by far than any that has preceded him. Yet it is equally clear that there are marked discontinuities between the ugly city, the dominant “inferential” philosophical modes of thought, the “deposit of all ages” that whose heterogeneity dwells within the present, and the evolved male subject who has yet to realize his ability to coordinate all of these contending forces. As Pater exclaims, “What an interesting period . . . is this we are in.” Yet the “aesthetic life” somehow eludes this “interesting” moment, perhaps because it must always remain out of sync with the present to which it should belong.

Bénédicte Coste, University of Burgundy: “Walter Pater: French Continuity and Discontinuity”

This presentation seeks to reassess the relationship of Walter Pater to France and to French writers, by distinguishing his relationship to a place he visited on several occasions and his relationship to French literature which he was an avid reader of. In his essays as well as in his fiction Pater establishes what could be termed a discontinuous relationship to French culture eerily divorced from contemporaneity and yet steeped in it. A reader of French new fiction embodied by Zola and the Goncourt brothers, he mainly concentrated on established and canonical writers such as Hugo, Mérimée and Pascal, or the now lesser-known Octave Feuillet and Ferdinand Fabre. France also provided him with museums abounding in paintings of the Renaissance, but also in modern paintings that he could have seen in the Salon de Paris or the Salon des Refusés, newly created by Napoleon III in 1863. I shall thus concentrate on tracing the tenuous and discontinuous link between Pater and French culture that fed his writings from the beginning.

Kenneth Daley, Columbia College, Chicago: “The Problem of ‘Feuillet’s La Morte’”

Since the publication of the second edition of Appreciations (1890), readers and critics have questioned, and most have lamented, Pater’s decision to replace “Aesthetic Poetry” with “Feuillet’s La Morte,” a review of the contemporary French novel that Pater first published in December 1886 in Macmillan’s Magazine. In relation to the other essays in the volume, the review seems a very different kind of work – more a typical Victorian book review than a Paterian appreciation – stringing together a series of passages from the novel with little of Pater’s own commentary and expression; “significant only of a certain catholicity of taste, and bear[ing] but few traces of his own temperament,” writes A.C. Benson in 1906. “[I]t is rather a problem why he eventually included this study in the Appreciations at all.” With an eye toward the conference theme of continuity/discontinuity in Pater’s work, this paper takes up the problem of “Feuillet’s La Morte.” The review essay itself has received scant critical attention. Might we draw any connection between it and the rest of the book? Or is it utterly anomalous, a radical discontinuity? What relation, if any, does “Feuillet’s La Morte“ have with “Aesthetic Poetry,” an essay that Pater reworked considerably from its earlier 1868 incarnation, attenuating his earlier anti-religious expressions, expunging those he could not revise. Is the Feuillet essay consistent with Pater’s apparently changed attitude toward Christianity and religious belief? What does Pater’s editorial decision suggest about his (changing?) attitude toward French fiction as an object of censorship in the English periodical press?

Michael Davis, Le Moyne College: “Castration, Incorporation and Queer historiography in ‘Notes on Leonardo da Vinci’”

For a number of years now I have been engaged in a large project tracing Pater’s development as a queer theorist through his early essays. Following a premature foray into Pater’s 1869 essay “Notes on Leonardo da Vinci” at the last Pater conference at Rutgers, in which I treated Pater’s famous passage on the Medusa’s head as an image of same-se ideation, I have since gone back to and revisited Pater’s prior, 1868 essay “Poems by William Morris.” I am currently working now on a re-reading of Pater’s next essay “Notes on Leonardo da Vinci” and propose for the Paris conference to show not only the continuity in Pater’s thinking about the subject of same-sex desire from the one essay to the other but also and moreover the discontinuity. In “Notes on Leonardo da Vinci,” Pater turns for the first time to a queer artist and analyses now for the first time the growth of the queer artist’s mind, to re-appropriate Wordsworth’s famous phrase and conceit. In describing that growth, Pater constructs a substantial psychoanalysis of Leonardo, together with an analysis of the ways in which cultural forms and practices participate in the formation of sexual subjectivity—supplementing the knowledge he had constructed in “Poems by William Morris” and engages in psychoanalytic readings of Leonardo’s art, much as Freud later will. Pater’s thinking comes to a “head” first in the image of the Medusa’s head, in which Pater takes full measure of the significance of the psychoanalytic principle of castration particularly as it figures in queer subjectivity. But in tracing the growth of Leonard’s mind he is also of course developing his own “latent intelligence,” his own queer theorizing and so the Medusa’s head functions also as a self-reflexive image, as I have suggested, of his own efforts at same-sex ideation. Pater’s thinking comes to a second major head in the head of the Mona Lisa: “hers is the head upon which ‘all the ends of the world are come.’” Like his meditation on the Medusa’s head Pater’s meditation on the Mona Lisa marks a major moment in his development of a queer theory. Whereas the former is largely concerned with the fantasy of castration (a cutting off from the body) the latter is largely concerned with a fantasy of incorporation (a withdrawal into the body), in both cases, notably, the female body. In that passage Pater radically reimagines the queer historiography he had described in “Poems by William Morris. Whereas in the earlier essay he had subscribed to a largely Hegelian model of history that was linear, developmental, and teleological, he now advances a “incorporational” model that is non-linear, nontranslational, and all-inclusive. In the Mona Lisa Pater imagines a queer subject free and at large in an unlimited queer landscape that is at once spatial and temporal.

Dennis Denisoff, Ryerson University: “’One Continuous Shelter’: Pagan Ecology in Marius the Epicurean”

The hero of Walter Pater’s Marius the Epicurean is surprisingly inert for somebody who is supposed to be on a journey. He delays for three days before even beginning his travels and then comes across as far less the adventurer on a path to self-discovery than a piece of driftwood caught in a stream. “Surrender[ing] himself, as he walked, to the impressions of the road,” Marius does not actively choose to venture forth to Luca, so much as find that his journey “brought him” there. And Luca itself is full of lethargic cottagers who, having lingered a moment on the threshold of their homes, “went to rest early” (160). The lethargy of the novel’s characters, I wish to suggest, accords with Pater’s exploration of the permeable boundaries of the self, the human, and the nonhuman. More specifically, I wish to turn to recent eco-pagan scholarship to argue that Pater’s novel, more than simply referencing elements of classical paganism, outlines a pagan notion of ecological continuity that was both historical and engaged with the pagan interests of his own time. In The Renaissance, Pater famously criticizes thosewho go “to sleep before evening” (250) such as the locals of Luca in Marius the Epicurean. The listlessness of Marius and the other humans in the novel, however, is countered by the energy of the environment itself. Even after the villagers have gone to rest, “there was still a glow along the road through the shorn cornfields, and the birds were still awake about the crumbling grey heights of an old temple: … you could hardly tell where the country left off in it, and the field-paths became its streets.” Here, Pater portrays the rural and the urban as part of a single, unselfconscious ecology that fuses animals, plants, and architecture. Pater does not mark this ecology as explicitly pagan; rather, he presents a trans-species comingling that accords with the earth-based, animist spirituality on which classical and Victorian paganism was founded. Thus, in Luca, “the rough-tiled roofs seemed to huddle together side by side, like one continuous shelter over the whole town” (160)—reconfiguring its individual denizens into a mutually reliant, ecological network that includes both natural and cultural elements.

Stefano Evangelista, Trinity College, University of Oxford: “Walter Pater’s Love of Letters”

By his own admission, Walter Pater was a bad letter-writer. He did not have a large circle of correspondents and the letters that have come down to us (collected and edited by Lawrence Evans in 1970) are mostly perfunctory in nature: business-like, formal, bland. Few of them reveal much about Pater’s intellectual life, his reading, travels, friendships or emotions. Pater seems either to have disliked letterwriting or to have mistrusted the epistolary genre as a medium of intimacy. It is partly due to the thinness of his extant correspondence that Pater has proved such an elusive subject for biographers and critics (including recent queer critics), the absence of an epistolary archive contributing to the myth of Pater as ‘the mask without the face’, made popular by Henry James. Yet Pater seems to have been very interested in reading new editions of collected letters, and he drew on them repeatedly in his work as critic. This paper examines Pater’s use of letters with specific reference to ‘Winckelmann’ (1867) and ‘Style’ (1888). Both essays appeared, in their original periodical publication, partly as reviews of volumes of correspondence, respectively by Winckelmann and Flaubert. The epistolary pre-history of these essays was erased by Pater as he collected them in volume form; but, even in their revised versions, “Winckelmann” and “Style” rely on citations from letters to reveal some of their most radical meanings, especially relating to sexuality. In my analysis I will pay particular attention to the productive tensions (or, to put it in the language of the conference theme, the continuities and discontinuities) between the epistolary and essayistic forms, the textual status of letters as intermediaries between the private and public spheres, and the role of intimacy in Pater’s construction of his biographical subjects.

Anne-Florence Gillard-Estrada, University of Rouen: “Walter Pater and Contemporary Art Critics: Dis/Continuities”

This paper aims at exploiting some of the fascinating corpus of periodical art criticism of the early 1860s onward, concentrating in particular on the reception of contemporary representations of Antiquity. In the wake of Elizabeth Prettejohn’s examination of Art for Art’s Sake and Rachel Teukolsky’s study of Victorian Art Writing, it aims at contributing to the exploration of contemporary art criticism through the study of recurrent notions such as the “indeterminate,” the “undefined,” the “obscure” or the “sub-conscious,” as well as through the dialectical emphasis on human form and on the human psyche. Such criticism in fact denotes tensions between the surface and what lies underneath, or between constructions of the ancients’ subjectivity and modern subjectivity—concerns that are central in the writings of some painters as well. However, beyond the oft-mentioned formalist rupture with the “subject,” or with narrative and morality, Walter Pater and a number of other prominent art critics brought up some kind of discontinuities as far as the conception of the human subject was concerned. Indeed, both the human form, which is so significant in these canvases, and critical discourses relating to them evoke complex meanings. Such representations recurrently appear as unfathomable while criticism turns into poetical recreations that give special value to creative suggestiveness. That mode of writing, then, becomes a near-verbalization of the erotic fantasies and the anxieties that were precisely at stake within the decidedly opportune and yet highly paradoxical “Greek” subject.

Lesley Higgins and David Latham, York University, Canada: “The Later Pater: The Choice of Copy-Text for The Collected Works of Walter Pater”

Considering the future directions of scholarship for Victorian literature, Andrew Stauffer warns that no Victorian “will long command serious critical attention without solid editions upon which new generations of readers can be raised,” adding that such “editorial work and textual criticism are not optional, second-order exercises to be performed after critical fame is secure: they are absolutely fundamental to establishing the existence of a poet for a modern audience of critics and students” (527). However much we Victorianists may feel Pater’s reputation is safe and secure, we have waited much too long to tackle that “absolutely fundamental” scholarship required as the foundation for serious criticism. Our first exercise in considering the supervision of a scholarly edition of Pater’s Collected Works for Oxford University Press was to compare different editions of the texts published during Pater’s life. For our presentation, we wish to focus on this preliminary study of textual variants, a study that we expect will change the way in which many of us have been reading Pater. What we have learned will dispel the myth that the first iteration was always his best because he was “fresher” when closer to his original inspiration and that he too often shied away from controversy when he revised his works. We will focus on the exceptional revisions that have troubled us, revisions that raise questions about Pater’s judgement. The 1893 revision of the penultimate sentence of the “Conclusion” to the fourth edition of The Renaissance, revising “art for art’s sake” to “art for its own sake,” looks less striking than the original, suggesting a retreat from the crusading efforts of Gautier and Swinburne; however, it typifies Pater’s concern with the unity of his book: the revised penultimate sentence of his “Conclusion” returns us to the similar phrasing of “for their own sake” in the penultimate sentence of his “Preface.” The 1890 replacement of “Aesthetic Poetry” with “Feuillet’s ‘La Morte’” in the second edition of Appreciations, only one year after it was published, is another exceptional example, one that suggests Pater’s profound concerns for continuity and discontinuity; moreover, it is an example that raises problematic questions that suggest the need for flexibility in our choice of copy-text.

Daichi Ishikawa, Keio University, Tokyo: “A Great Chain of Curiosity: Pater’s ‘Sir Thomas Browne’ and its Nineteenth-Century British Context”

It has been 20 years since Linda Dowling, in a brief note to her 1994 book, attended to Matthew Arnold’s classification of the word ‘curiosity’: namely curiosity as “a high and fine quality of man’s nature, just this disinterested love of a free play of the mind on all subjects, for its own sake,” and as “a rather bad and disparaging one”. My paper attempts to reveal how Pater helped to rehabilitate the positive aspect of curiosity in late nineteenth-century Britain and then Europe, with particular emphasis on his recurrent notion of curiosity, sympathy and (as Matthew Potolsky has emphasised) community, which permeates his essays such as “Sir Thomas Browne,” “Leonardo da Vinci,” “Postscript [Romanticism],” “Charles Lamb,” and others. As Pater suggests, “Browne’s works are of a kind to directly stimulate curiosity about himself’. Entangled in such a great chain of “English men of letters” as Samuel Johnson, S. T. Coleridge, Charles Lamb, Leslie Stephen, J. A. Symonds, Edmund Gosse, Lytton Strachey, or Geoffrey Keynes, Pater consciously or unconsciously formed part of the long nineteenth-century enthusiasm for Sir Thomas Browne “the humourist, in the old-fashioned sense of the term, [. . .] to whom all the world is but a spectacle in which nothing is really alien from himself”. At least in the Victorian period, this curious vogue for Browne was nurtured in authoritative book form and also by the rapidly developing media of periodicals. It is therefore not incidental that Symonds’s article on Browne appeared in the Saturday Review on 25 June 1864 (between Pater’s “Subjective Immortality” and “Diaphaneitè”), and was to form, with revisions, the introduction to his Camelot Classics edition of Browne’s writings of 1886, the same year Pater’s essay on Browne was published in the Macmillan’s Magazine. Symonds’s letter of 13 June 1886, writing: “I read Pater’s essay. . . . The best passage was a curious discourse upon Browne’s ‘Letter on the Death of a Friend’,” obliquely testifies how the nature of their literary correspondence directed the discussion about curiosity and its textual transmission through culture between the epoch of “concentration” and that of “expansion,” the continuous and the discontinuous.

Martine Lambert-Charbonnier, University Paris-Sorbonne: “Discontinuity in biography: are there different Paters?”

Different biographical approaches have resulted in various pictures of Walter Pater—or different “Paters”—being drawn, according to changing preoccupations and critical methods. Those pictures are discontinuous or even contradictory, sometimes conjuring up the portrait of a solitary and ascetic character, then presenting him as an aesthete with repressed desires and homoerotic inclinations. More recently, he was portrayed as an ambitious man, responsive to the ideas of his time and keen to make his own contribution to literature. The biographer wishing to write the life of Walter Pater is faced with discontinuity in the reports and interpretations of his character. Moreover in the case of Pater who wrote critical and imaginary lives of many characters, his own essays are precious, though discontinuous, sources of information, suggesting—though indirectly or even fictionally—self-portraiture. The concept of “process,” as defined by sociologist Norbert Elias and reinterpreted by Idalina Conde for the specific field of biography , paves the way for a possible synthesis as it views the biographical narrative as an ongoing construction gradually integrating different levels of figuration, whether factual or symbolical. Elias’ concept of history as open to a “horizon of possibilities” is particularly relevant for Walter Pater who cultivated open-mindedness and sought as many influences as possible from various times and cultures. The emphasis on interaction and on reception, which fits in with Laurel Brake’s approach to Pater’s biography, will allow us to further develop the image of Pater as a man in grasp with the intellectual and artistic issues of his time.

Adam Lee, Sheridan College, Canada: Trace, “Race, and Grace: The Influence of Ernest Renan’s Souvenirs D’enfance et de jeunesse on Pater’s Gaston De Latour”

‘La foi a cela de particulier que, disparue, elle agit encore. La grâce survit par l’habitude au sentiment vivant qu’on en a eu. On continue de faire machinalement ce qu’on faisait d’abord en esprit et en vérité. Après qu’Orphée, ayant perdu son idéal, eut été mis en pieces par les ménades, sa lyre ne savait toujours dire que ‘Eurydice! Eurydice!’ (Renan, Souvenirs) Critics have long noted Renan’s influence on Pater, especially in his first published essay, “Coleridge’s Writings” (1866), where Renan is credited with possessing the “relative spirit.” Billie Inman and others have found Renan’s Vie de Jésus (1863) as particularly influential in exposing to Pater the metaphysical weakness of Christian dogmatism. More recently, acknowledging this early similarity between the two writers, John Coates in « Pater as Controversialist » (2011) argues that a separation between them arises as Pater’s writings from the mid-1880s reveal a greater sympathy towards Christianity. And yet remarkable similarities can still be traced between Renan’s memoir, Souvenirs d’enfance (1883), and Pater’s novel Gaston de Latour (1888). Both books are personal narratives of a youth’s development to manhood, whose character is defined by physical, emotional, and intellectual influences, often recognized as traces of the past. Both heroes grow up surrounded by ecclesiastical architecture, Renan amidst the ancient seminary of Tréguier, and Gaston (like Pater) in the shadow of a famous cathedral. Both characters are affected by his particular blend of race. Renan explains he is Gascon on his distaff side, allowing him to smile at life’s difficulties, while on his father’s side he is a Celt from Breton, rendering him an idealist. The opening pages of Gaston foregrounds “race” as a determinant to character more than any of Pater’s works, although the picture is complicated, as his reference to the Biblical Esau and his stolen birth-right suggests. Gaston is said to be of the northern region of Beauce while his name means a man from Gascony; and spending time in Montaigne’s tower, as “de La-tour” might suggest, further makes him an intellectual son of Bordeaux. Both Renan and Gaston, born into a strong clerical tradition, within and without (race and place), feel an early calling towards the priesthood, which, though later mitigated, continues to inform their character. The lyre of Orpheus, struck through their early experiences, continues to resonate; calling for Renan to remain a “priest in spirit,” calling Gaston towards an unfulfilled return.

Sara Lyons, University of Kent, UK: “‘Only the Thorough Sceptic Can be the Perfect Saint’: Altruism, Agnosticism, and Pater’s Marius the Epicurean”

As Thomas Dixon has recently shown, the popularisation of Auguste Comte’s coinage, “altruism,” helped to render the case for an exclusively secular morality tenable and even compelling in the late Victorian period. Nonetheless, the secularist agenda inscribed within the term meant it was initially greeted with suspicion by the devout, who often regarded it as an attempt to “out-Christian” Christianity. In Britain, “altruism” was also frequently conflated with “agnosticism,” and some perceived both terms as sly pieces of secularist code which, when cracked, simply amounted—in Frances Power Cobbe’s assessment—to a kind of “magnanimous atheism.” In 1877, Cobbe mocked the transvaluation of Christian values by which the “agnostic” claimed the moral high ground: “If we are to accept his own statement of the case, the Agnostic has completely turned the front of the theological battle. It is now the Pagans who have seized and hold aloft the sacred Labarum of Duty and Self-sacrifice … Only the thorough sceptic, we are assured, can be the perfect saint”. Focussing primarily on Marius the Epicurean (1885), my paper will analyse how Pater understood the distinction between secular and Christian ethics, particularly in relation to atonement theology and to ideals of altruism and self-sacrifice. The scandal over the “Conclusion” to Pater’s Renaissance in 1873 stemmed partly from a perception that his aestheticism represented a novel and peculiarly selfish variety of atheism; for instance, the Bishop of Oxford, John Mackarness, claimed that Pater’s acolytes would come to believe that “it is folly to disturb themselves for the sake of others” and dismiss “self-sacrifice” as “mere moral babble”. Marius has often been read as a complex palinode to the “Conclusion,” partly because its eponymous hero appears to find Epicurean philosophy lacking in moral depth and dies an exemplary Christian, at least insofar as he sacrifices his life for the sake of a friend. And yet Marius remains resistant to the idea of martyrdom even as he dies a martyr, and never renounces his Epicurean faith in the primacy of pleasure. Indeed, Pater suggests that Marius’s martyrdom is meaningful precisely because he sacrifices a life whose pleasures he appreciates fully and because he anticipates no “miraculous, poetic” reward; he is truly a Christian martyr because he remains an Epicurean. Moreover, Marius effectively deprives his Christian friend, Cornelius, of the opportunity to be a martyr because he (i.e., Marius) perceives nothing “glorious” in it and thinks it better that Cornelius marry and enjoy life. I trace affinities between the paradoxical, truly-Christian-because-Epicurean nature of Marius’s martyrdom and John Stuart Mill’s critique of Christian ideals of self-sacrifice in Utilitarianism (1861). More broadly, I will suggest that the interpretive difficulties that Marius poses for the modern reader—particularly the question of whether it ought to be read as a Christian novel—can be clarified when it is situated in relation to debates over “altruism” and “agnosticism” that animated the periodical press in the late 1870s and 1880s.

Nicholas Manning, University Paris-Sorbonne: “Unimpassioned Passion: Inner Excess and Exterior Restraint in Pater’s Rhetoric of Affect”

In spite of his claim that “the essence of all artistic beauty is expression,” passion is rarely presented in Pater’s criticism as playing an expressive or communicative role in either aesthetic experience or critical appraisal. In contrast to the critical “disinterest”—with its requirement of a generalized emotional equilibrium—central to Matthew Arnold’s criticism, excessive passion for Pater is rather a key part of the subjective mitigation of art within the individual mind. This internalized emotion gives rise to what Pater, in Plato and Platonism, calls a state of “unimpassioned passion”: an apparent affective disconnect, common to both the guardians of Plato’s Republic and the silently suffering Laocoön, which contrasts inner affective activity with outward, expressive passivity. Rather than the negative passivity of an expressivist model, however—according to which inner emotions which are not expressed become frustrated or lost—Pater presents such internalized passion as a positive, continuous source of lived and aesthetic intensity. Pater’s predominant use of “passion” rather than “emotion” in his discussions of art and literature is on this point revealing. This primary distinction, reflected in the terms’ respective etymologies, between passivity (passio) and activity (motio), frame two forms of affective engagement. We may see this Paterian model as an explicit revolt against the persuasive conception of pathos deployed by Plato in his condemnation of Sophistic rhetoric, and an attempt to cultivate an internal, subjective affect more closely linked to ethos (or in Paterian terms, “temperament” and “sensibility”). As Susan Jarratt has observed, “rather than act within a community to shape effective knowledge for the group, the Paterian rhetorician reports on knowledge already achieved through observation and internal intuition.” To found a rhetoric of emotion on a private encounter with language and the self is to propose a vision of both rhetorical appraisal and affective mitigation at profound odds with the communicative, persuasive, and thus potentially manipulative role of pathos common to much late nineteenth-century thought. Though this Paterian affective model seems initially then to highlight a rupture between interior affect and exterior expression, Pater makes use of it to generate an aesthetic continuity of inner, invisible passion and outward restraint, which traverses Western art and philosophy from Plato’s Republic, through Hellenic sculpture (Winckelmann’s consideration of Laocoön), up to the “temperance” of Renaissance art. Paterian “passion”, while appearing to instigate a profound affective discontinuity (as per a model of affect which values interpersonal communication), thus rather initiates an internalized meeting of subject and world, which occurs during the personal kairos of the ecstatic, aesthetic moment.

Catherine Maxwell, Queen Mary, University of London: “Air and Atmosphere in Walter Pater”

Following on from my recent article “Paterian Flair: Walter Pater and Scent” (2012), this paper will examine the related ideas of “air” and “atmosphere” in Pater’s writings, terms which can indicate a particular physical environment or a sense of place and its associated emotional tenor, but which are also used more figuratively, transcending narrow categories of time and place, to describe the ambience of a particular writer’s work, the characteristic quality of a group of writers, or the spirit of an age or movement. This paper will consider the way in which Pater uses ideas of “air” or “atmosphere” throughout his oeuvre starting with the essays included in Studies in the History of the Renaissance (1873) through to Plato and Platonism (1893), paying special attention to continuity and discontinuity (or innovation) in his usage. I shall show how ideas of influence and “sentiment,” a word of which Pater is particularly fond, are intricately bound up with his language of atmosphere, a case in point being his essay on “Joachim du Bellay”. I will also consider the synaesthetic qualities of Pater’s language as part of a larger meditation on his favoured expressive terminology, a terminology that tends to hover tantalisingly between literal, physical reality and figurative, spiritual, and metaphysical meaning.

Dominique Millet-Gérard, University Paris-Sorbonne: “Walter Pater: Beauty as a ‘poetic principle’ of continuity”

Through a combined reading of Marius the Epicurean and some of Pater‘s essays on aesthetics, we intend to examine how Beauty is the main principle of continuity between Antiquity, the Middle Ages, the Renaissance and modern times. We shall have to define Pater ‘s idea of the Beautiful, as a philosophical concept as well as a contemplative experience of beautiful things—whether natural or artistic—Including the part they play in the narrative. Pater’s idea of Beauty proves deeply “incarnated,” which is probably his main point of contact with Christian aesthetics and especially Roman Catholic liturgy. Taking into account Pater’s paradoxical fascination for some sort of ugliness, violence and provocation, we shall try to explain why Hans Urs von Balthasar, the learned Jesuit who wrote a superb essay on Hopkins, denies Pater any access to what he calls “theological aesthetics”.

Noriyuki Nozue, Osaka City University: “Pater’s Political Playing with Englishness in ‘Emerald Uthwart’”

“Emerald Uthwart” (1892) is quite challenging to Pater scholars. As Lawrence Evans states, it is “enigmatic” and “one of Pater’s most elusive stories,” while it has mainly been regarded as autobiographically motivated like “The Child in the House” (1878). I will suggest an importance of this later imaginary portrait in its exploration into, and subtle criticism of, military manliness and British imperialism. I will focus on “English,” an adjective employed so often throughout, with its implications slightly changing according to the context. Then Pater’s continuity and discontinuity with the contemporary conservatives and “Little Islanders” will be investigated. At the beginning of an earlier paragraph the narrator makes a summary of the protagonist’s life and death, putting emphasis on “English” features of his native village, its earth, flowers, houses and landscape; but at the end of the same part the adjective is replaced by the definitive article. This prefigures a change in Emerald’s mind, from his earlier satisfaction with his “English” surroundings, to indifference to anything called such. This is to be the case when Emerald’s last homecoming is described. Public school education, very “English” again, seems to have transformed the young boy’s mind and body, and made him ready for military activities. Pater looks sympathetic with its virtues, discipline and esprit de corps. This reading comes to be suspended, however, or even questioned by several brief episodes: Emerald’s reputed incapability of tears, his inability to understand the “triumph” of war, and his struggle to face death “manfully” as a civilian, but not a military officer. We must note a slight expression given for a reason for Emerald’s returning to “the scene of his disgrace, of the execution” and passing over it “unrecognized”: “for some change . . . in himself.” The significance is revealed in the following paragraph: Emerald’s indifference to the war and its glory, his love of the native place which is against imperialistic patriotism. In the previous paragraph “English” is used for the last time (“English shores”). Then the narrator drops it and uses the definitive article instead, for grass, flowers and earth. A last incident of Emerald’s honour regained implies a criticism on Pater’s part of the English military, the public’s desire of a “spectacle of war” and the journalism’s incitement for it. Pater is daringly anti-English here.

Amanda Paxton, York University, Canada: “The Theory of the Moment in a Comparative Perspective: Coleridge, Pater, and Bergson”

The “moment” is an aesthetic touchstone for both Samuel Taylor Coleridge and Walter Pater, albeit in diametrically opposed ways. My presentation correlates Pater’s and Coleridge’s respective notions of temporal dis/continuity with Henri Bergson’s theory of “duration” (durée) and the related notion of “the virtual,” a term used by present-day theorists to designate the quality of latent possibilities rather than concretely manifest realities. For Coleridge, art is a tool with which to fix the unfixable virtual, foreclosing ongoing temporal continuity into a singular, discontinuous moment. For Pater, art enables one to abandon oneself fully to the continuities of time and to what Deleuze calls the “coexistent multiplicities” within the becomings inherent in duration. This consideration of each writer in relation to duration will expand our understanding of Pater’s concept of the “moment” as articulated in the “Conclusion” to The Renaissance. Bergson’s “duration” posits each experience as being informed by all prior moments, with time constituting a continuous swarm of virtual potentialities that contribute to each instant’s manifestation. In the essay “Coleridge’s Writings,” Pater also declares as much: “Nature… provide[s] that the earlier growth should propel its fibres into the later, and so transmit the whole of its forces in an unbroken continuity of life.” He notes that Coleridge, intuiting yet resisting this process, is caught in “a situation of difficulty and contention” in his Romantic effort to “apprehend the absolute.” Taking “Kubla Khan” as a case study, I suggest that art functions for Coleridge’s speaker as a medium through which to pursue a discontinuous absolute by attempting to pinpoint a finality to the Bergsonian “moment,” to contain what Coleridge calls the “Dread Book of Judgment” within an aesthetic Pleasure Dome, and to “reclaim the world of art as a world of fixed laws” that can themselves stabilize the process of history into insularity. I argue that, in the Conclusion to The Renaissance, Pater inverts Coleridge’s attempt to rigidify the moment, and instead posits art as a vehicle for experiencing continuity rather than discontinuity. The resulting model of the moment reveals proliferating webs of infinitely related continuities arising from one another. Although Modernists are familiar with the significance of Bergson’s work for writers such as Virginia Woolf, my paper suggests that Coleridge and Pater, avant la lettre, were grappling with the implications of emergent, non-linear models of time.

Elizabeth Prettejohn, University of York, UK: “Pater and Sculpture: Between Ancient and Modern”

When Walter Pater’s two-part essay “The Beginnings of Greek Sculpture” first appeared in 1880, not even an archaeologist would have been able to predict the momentous shift that was about to take place in the understanding and appreciation of ancient sculpture. In the late 1870s archaic sculptures were just beginning to emerge from the excavations of the French on Delos and the Germans at Olympia, and it was not until 1886 and beyond that new excavations on the Acropolis at Athens brought to light the important series of archaic female figures at first called “Maidens,” later “korai”. These archaic finds would not only transform the scholarly study of ancient sculpture, but would also make a profound impact on the practices of the painters and sculptors of the first modernist generation of the early twentieth century. Those developments were still in the future when Pater began his phase of work on ancient sculpture, and in his essays of 1880 he refers instead to the recent discoveries of Heinrich Schliemann at Mycenae and Troy. This paper will argue, however, that Pater’s essays create intellectual structures of great subtlety and sophistication for the understanding and appreciation of pre-classical sculpture. His ways of thinking about the very earliest ancient art may paradoxically have shown the way for artistic modernism in the next generation. In his writings on ancient sculpture from 1880 onwards, Pater partly revises the earlier view of his essay on Winckelmann of 1867. Yet he also draws closer to Winckelmann’s achievement as he had himself described it. Like Winckelmann he is able to provide significant insight into works of ancient art that had not yet come to light; again like Winckelmann, his explorations of the art of antiquity are of the utmost relevance to that of modernity.

Robert M. Seiler, University of Calgary, Canada: “The Book as Aesthetic Object”

The edition of letters that I have undertaken builds on the Letters of Walter Pater (1970), which was systematically researched and meticulously edited by the late Lawrence Evans and handsomely published by the Clarendon Press. Evans’ edition, the only collection of its kind, has been out of print for some time. I am picking up where Evans left off, as it were, and will strive to produce a text that will be judged comprehensive, accurately transcribed, and adequately annotated. In this presentation I reflect on several interrelated questions: How important is the theme running through The Book Beautiful: Walter Pater and the House of Macmillan (London, 1999) to volume 9 of The Collected Works of Walter Pater? How central is Pater’s interest in the “aesthetic book” movement and his concern that his own books be beautiful (as revealed in his correspondence with his publisher) in the context of his entire correspondence? Is it the major theme or are there others that are equally important? In short, what are the major themes of Pater’s correspondence? As well, how do these themes relate to one another? Such a project is not without challenges. For example, determining what constitutes a comprehensive collection of Pater’s correspondence is problematic. Early biographers offered opposing views on the matter. In Walter Pater (1906), A. C. Benson claimed that Pater wrote few letters and never kept a diary (185), whereas in The Life Of Walter Pater (1907) Thomas Wright declared (I. ix) that Pater wrote an enormous number of letters, as many as 400 to one friend. If, as Evans speculates (p. xvii), we assume that, from the age of nineteen, Pater wrote one letter per week, that is, above social notes and business letters, he would have written over 1,800 letters. The letters that have survived seem all the fewer when we think of the collections of, say, D. G. Rossetti, A.C. Swinburne, and Oscar Wilde. My edition will reprint (a) the 272 letters that Evans published in Letters of Walter Pater; (b) 10 of the letters I printed in Walter Pater: A Life Remembered (1987); (c) 189 letters I published in The Book Beautiful; and (d) 35 fugitive (autograph) letters that have surfaced in recent years, of which about 20 have appeared in articles, for a total of about 500 letters to 95 correspondents. Five letters will be published for the first time. This edition will also include (in the Appendix A) 45 fragments of letters that appear in biographies, memoirs, and miscellaneous works. As we know, Pater’s letters are fairly routine and business-like, often perfunctory, even those addressed to his to closest friends (he admitted that he was a poor letter-writer). They nevertheless enrich our understanding of his character and personality: they throw light on such important topics as his social life; his mentoring, in terms of counselling young writers, reading their manuscripts, and writing testimonials; his take on public events, including controversies; and his career as a philosopher at Brasenose College; the conception, composition, publication, revision, and reception of his works, especially his campaign to produce books as aesthetic objects (the Pater-Macmillan letters figure hugely in this collection) and to forestall negative criticism. It is on this last topic—Pater’s enthusiasm for the idea of books as aesthetic objects and his dedication to producing beautiful books—that I focus here. In short, I propose to reflect on Pater’s preoccupation with “giving my book[s] the artistic appearance which I am sure is necessary for [them]” (LWP, 10), as revealed in his correspondence.

Jonah Siegel, Rutgers University: “Pater’s Houses: ‘The Afterlives of an image’”

Homesickness may be the most clearly marked disease in Pater. Nostalgia experienced as something like a physical fact is the source of the uneasy motion that motivates so many of his most memorable figures, from Florian in “Child in the House,” to Marius, who needs to bury his own home and ancestral shrines before his narrative can come to and end, to Winckelmann, who faces down a strange “inverted home-sickness” when he leaves Rome for Vienna on his ill-fated final voyage. Unsurprisingly, it is above all the inversion of homesickness caused by Rome that we may read as most typical. The longing for nostos is not in that sense a simple organic metaphor for Pater; what is desired is not a return to a natural source, but to a place made or claimed as home. This paper is an analysis of returns to the figure of the home by three readers of Pater who relayed his sensibility to the twentieth century. It is interested in the continuity of the writer’s work in other authors, in other texts, and especially in the ways in which the metaphor of the home becomes filled in and made something different. Works by Vernon Lee, Mario Praz, and Ernst Robert Curtius acknowledge and play with the imagination of culture they inherited from their acknowledged precursor, in particular the ways in which the figure of the house allows for a particularly poignant vision of cultural transmission or continuity after a period of rupture. And so, while I will touch on Vernon Lee’s rewritings of “The Child in the House,” and on her creation of a home in Florence that could be taken as a version of the ideal laid out in Marius when Praz saw it in the 1920s, my focus will be on the evocations of Pater in two texts shaped by the trauma of the Second World War: Praz’s The House of Life (1958) and Curtius’s European Literature and the Latin Middle Ages (1948).

Ulrike Stamm, Humboldt-University, Berlin: “Pater and the Dis/Continuities of cultural alterity”

In Pater’s writing the question of influence plays an important role as has been shown in Walter Pater: Transparencies of Desire. Pater’s historical thought seems to be obsessed with the idea of the transference of ideas from one period to another or from one geographical unit to another. As strangeness generally is presented as a positive factor, and cultural translation as a process in which it is precisely the contact between diverse cultural worlds that has an invigorating effect one could conclude that Pater has a positive concept of alterity. Viewed in connection with the fact that Pater’s thought developed at the time of high colonialism favouring the idea of clear borders between cultures and following the ideal of cultural integrity, it is furthermore remarkable that the idea of the unity of culture does not play a prominent role for Pater. On the other hand Pater does not see cultural translation as an unproblematic process. He has a clear understanding of the problems inherent in the transference of ideas, which either can become a sort of hollow imitation producing a culture of dead artificiality or can turn out to be only a form of projection. The appropriation of the other and the fascination of the foreign can in this way obstruct access to one’s self and therefore not allow for real alterity. This projective relationship towards the foreign is therefore similarly fated to result in destruction as are all xenophobic notions of the other, and Pater shows that both approaches prevent a productive reception that enables new cultural developments. In my paper I want to follow up these questions asking especially which model of cultural transference he presents. In this way I want to read Pater in the context of recent post-colonial theories, situating his thought in the historical time of colonialism and exploring his reaction to some main concepts of imperialism. One final question will be whether one of the main problems preventing cultural contact in Pater’s literary world is the fact that the tension between the self and the other is lost as the other is actually absorbed by the self. If this were the case, alterity, which at first sight seems to be so favoured in Pater’s imagination, would be more or less excluded as the difference between self and other disappears.

Rachel Teukolsky, Vanderbilt University: “Walter Pater and Sensation”

“Sensation” is a word that pervades Pater’s writings and serves as a cornerstone to his aesthetic philosophy. His embrace of sensation, sensuousness, and other forms of erotic embodiment has often been interpreted as his rebellion against restrictive Victorian social and religious codes. Yet despite sensation’s significance for Pater, few scholars have considered his potential links to the “sensation” phenomenon of the 1860s, made notorious by the sensation novels of Wilkie Collins and Mary Elizabeth Braddon, among others. Pater’s essays began to be published in the late 1860s, when the sensation craze was still hotly debated in the public sphere. In this paper, I consider both the surprising continuities and revealing discontinuities between these two different, yet related, kinds of “sensations.” The current scholarly divide between aestheticism and sensationism reflects modern assumptions about high art versus mass culture. Paterian sensation is seen as the preserve of the educated aesthete, looking at art with a kind of reflective detachment. Mass-cultural sensation, by contrast, has been coded by critics from the 1860s to the present day as a more inappropriate somatic response to thrills and chills—the body unregulated and animalistic. Yet in some senses this divide between high and low is more entrenched now than it was in the nineteenth century. For an 1873 reviewer of Pater’s Renaissance, “The housemaid who revels in the sensation novels of the ‘London Journal’ holds with Mr. Pater—only less consciously—that it is the pulsations that make life worth the living.” Victorian critics were aware that Pater’s promotion of physical pleasure brought him dangerously close to the provinces of mass culture—aligned with women, working-class people, and others defined through bodily excess. The paper will argue that Paterian sensation (especially in The Renaissance) does have ties to more mass-cultural incarnations, found not only in novels but also in paintings, melodramatic theatre, and other kinds of thrilling spectacles. Yet I will also explore important discontinuities, such as Pater’s focus on men, versus the usually female focus of sensation arts; and the role of ascesis in potentially mitigating some of Pater’s sensational tropes.

Carolyn Williams, Rutgers University: “Textual Time Zones”

In Transfigured World, I concentrated on two of Pater’s favourite visual representations for the relations between continuity and discontinuity—one, the seemingly progressive time-line with “high” points nevertheless representing revivals of the classical past, and the other, the composite figure of “relief,” in which a figure is raised against a flat background in order to suggest the interpenetration of past and present, continuity and change (a topic lately renewed and extended brilliantly by Lene Østermark-Johansen). More recently, I’ve come these issues by thinking about music and visualization in Pater in relation to the “tableau moment” of melodrama (in “Walter Pater, Film Theorist”). In that essay I find coherence between Pater’s emphasis on visualization in the moment and the aesthetic patterning of melodrama that leads directly into cinema. It seems possible that narrative with intermittent, punctual visualization should be understood as a nineteenth-century period style.

I would like to begin with a few reflections on past work – and the ways I’ve found to approach the conference theme. Then I would like to turn to the question of literary genre, particularly to the way Pater uses intertextuality as an interdisciplinary or inter-generic marker of discontinuity, within the overall continuity of his present text. I will use Marius the Epicurean as a test case, returning to the question of Pater’s profoundly aesthetic “vision” of history through the way he handles allusion, quotation, citation, and intertextuality. As all lovers of Pater know, he does not allow intertexts to be buried or “absorbed” within his present text so much as he sets them off, displaying them as disruptive, letting the seams show as he moves us from one textual time zone to another. Thus is the old set off against the new, and the disruption of moving from present text to past text (and back) is both jarring and beautiful.

Design for Windrush printed fabric by William Morris, 1881-83 (Identification from Linda Parry, ed.: William Morris, Abrams, 1996, ISBN 0-8109-4282-8, p. 265).

Source: Planet Art CD of royalty-free PD images William Morris: Selected Works (see online)

Thomas Albrecht is an Associate Professor of English at Tulane University in New Orleans, teaching Victorian literature, Comparative Literature, and literary criticism and theory. He is the author of The Medusa Effect: Representation and Epistemology in Victorian Aesthetics (SUNY Press, 2009) and the editor of Selected Writings by Sarah Kofman (Stanford University Press, 2007). He has contributed several short pieces to the Pater Newsletter. He is currently at work on a book about the relationship between ethics and aesthetics in the work of George Eliot, and last year published an essay on cosmopolitanism in Eliot’s novel Daniel Deronda in the journal English Literary History (ELH).

Kit Andrews is Professor of English at Western Oregon University. He has written articles and book chapters on Walter Pater, Walter Benjamin, Michael Field, and Watteau. He is currently researching the reception of German Idealism in nineteenth-century British literature and philosophy. He has recently published an article on Walter Pater as Oxford Hegelian in The Journal of the History of Ideas, and another in Literature Compass on Carlyle and Fichte.

Pascal Aquien studied at the École Normale Supérieure of Saint-Cloud and is currently teaching as a Professor of 19th- and 20th-century English literature at Paris-Sorbonne University. He specializes in poetry and wrote a doctoral thesis on W. H. Auden (W. H. Auden de l’Éden perdu au jardin des mots, L’Harmattan, 1996) as well articles and books on English poetry. He translated 19th- and 20-th century poetry, such as Swinburne, Poèmes choisis (éd. bilingue, Corti, 1990) and Matthew Arnold, Éternels étrangers en ce monde (éd. bilingue, La Différence, 2012), and edited The Complete Works of Thomas de Quincey for the Bibliothèque de la Pléiade collection (Gallimard, 2011). He has also worked extensively on Oscar Wilde, publishing several editions and translations of Wilde’s plays and works with Flammarion, and prefacing Wilde’s Works for the Pléiade (Gallimard, 1996). He wrote also a biography, Oscar Wilde. Les mots et les songes (Aden, 2006). Pascal Aquien is the editor of the journal Études Anglaises (Klincksieck, Les Belles Lettres). He is currently Vice-President of the Scientific Council of Paris-Sorbonne University.

Sylvie Arlaud completed a PhD in German and Austrian Literature in 1999 on the English influences on Hugo von Hofmannsthal and the Viennese literary modernity and is a lecturer in German and Austrian Literature at the University of Paris Sorbonne. Her main fields of research are the cultural transfers between German-, French- and English-speaking countries at the turn of the nineteenth century (Wiener Moderne) as well as the history and theory of drama (nineteenth century-2013). She wrote Les références anglaises de la modernité viennoise (2000) and a number of articles on Shakespeare and the German stage, Hofmannsthal’s and Molière, Hermann Bahr, or Viennese architecture and its reception in France.

Megan Becker-Leckrone, former editor of The Pater Newsletter (2006-2011), is Associate Professor of English at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, where she specializes in the history of literary/critical theory and late-Victorian literature and culture. Her book, Julia Kristeva and Literary Theory was published by Palgrave in 2005. She has published several articles on movements and major figures in critical theory, and on literary figures such as Walter Pater, William Wordsworth, Oscar Wilde, among others. Along with fellow Paterian, Kate Hext, she serves as a book review editor for Victoriographies, published by Edinburgh University Press.

Elisa Bizzotto is senior lecturer in English Literature at IUAV University of Venice. Her research focuses on Victorian, late-Victorian and pre-Modernist literature and culture. She has written on Walter Pater, Oscar Wilde, Vernon Lee, the Pre-Raphaelites, Aubrey Beardsley and other late-Victorian and early-twentieth-century figures. She is the author of La mano e l’anima. Il ritratto immaginario fin de siècle (2001) and the co-author of The Germ Origins and Progenies of Pre- Raphaelite Interart Aesthetics (2012). She has co-edited Dalla stanza accanto. Vernon Lee e Firenze settant’anni dopo (2006) and the first Italian edition of the Pre-Raphaelite magazine The Germ (2008).