Anti-Catholicism in the British Isles in the 16th-21st Centuries

Horaire : 09h00-18h00

Lieu : Maison de l’Université | Salle divisible nord | Mont-Saint-Aignan

Cette journée d’étude est organisée par l’ERIAC et le GRHis, avec le soutien du GDR Mondes britanniques.

ARGUMENTAIRE | ARGUMENT

En septembre 2010, lors de la visite officielle du pape Benoît XVI au Royaume-Uni, une association « Résistons au Pape », qui rassemblait des humanistes, des athées et des groupes anticléricaux, organisa plusieurs manifestations pour protester contre la visite pontificale. À Édimbourg, capitale écossaise, le célèbre pasteur nord-irlandais Ian Paisley distribua avec ses partisans des pamphlets qui dénonçaient la visite de l’« Antéchrist » et rappelaient les différents scandales qui avaient récemment éclaboussé l’Église de Rome.

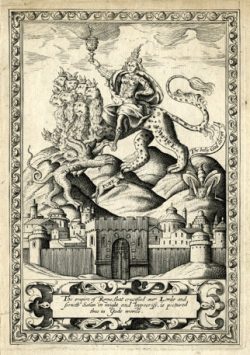

Dans son ouvrage Britons. Forging the Nation 1707-1832, paru en 1992, l’historienne britannique Linda Colley a démontré le lien fondamental entre identité britannique et protestantisme depuis l’époque moderne. En effet, la question confessionnelle au Royaume-Uni dépasse largement le cadre religieux strict. Depuis la Réforme, le protestantisme, et, partant, l’anticatholicisme, ont joué un rôle central dans l’invention de la Grande-Bretagne. Car ce dernier ne peut se résumer à une opposition théologique contre le catholicisme mais incarne plutôt une contestation qui embrasse divers domaines sociaux et culturels. Une rapide typologie des formes que revêt l’anticatholicisme depuis le XVIe siècle permet de distinguer plusieurs plans. Il existe, tout particulièrement depuis le XVIIe siècle, un anticatholicisme de type étatique qui pénalise politiquement, économiquement et socialement les papistes – c’est le cas des Penal Laws du XVIIIe siècle et des lois qui excluent les catholiques du droit de suffrage et de la représentation politique. À cela s’ajoute un anticatholicisme populaire qui se manifeste pendant les célébrations de Guy Fawkes Day et par la formation de sociétés ultra-protestantes diverses. Ce type d’anticatholicisme va de pair avec un anticatholicisme « socio-culturel » diffus qui véhicule l’image de la religion romaine comme porteuse de principes contre-nature (le célibat des prêtres par exemple) et qui maintiendrait les ouailles dans l’ignorance (tyrannie du clergé). L’adhésion de la majorité des sujets britanniques protestants à ce rejet du catholicisme (en témoignent le succès et les nombreuses rééditions du martyrologe protestant de John Foxe) apparaît comme un facteur de cohésion puissant pour une Britishness commune.

Comme l’a écrit l’historienne Yvonne Werner en 2013, « le démantèlement progressif de la législation sur la conformité religieuse obligatoire a conduit à la politisation des questions religieuses ». En conséquence, depuis le milieu du XIXe siècle, on observe au Royaume-Uni l’émergence de sociétés ultra-protestantes qui n’ont eu de cesse de réaffirmer l’importance des principes de la Réforme comme fondement de l’identité britannique. Après la Seconde Guerre mondiale et la sécularisation accélérée de la société britannique, ce sont des groupes militants d’athées et « d’humanistes » qui ont inventé de nouvelles formes d’anticatholicisme.

Cette journée d’études, qui rassemble des universitaires britanniques et français, explorera en langue anglaise les différentes facettes de l’anticatholicisme depuis la Réforme protestante du XVIe siècle. Le propos couvrira l’ensemble des îles britanniques et offrira également en contrepoint un regard sur l’antiprotestantisme en France au début du siècle dernier.

In September 2010, when Pope Benedict XVI came on an official State visit to Britain, the ‘Protest the Pope’ umbrella group, bringing together humanist, atheist and secular groups prepared several actions and demonstrations against the papal tour. In Edinburgh, Rev. Ian Paisley and his ultra-Protestant supporters objected against the venue of the ‘antichrist’ and distributed pamphlets listing ‘recent scandals’ with the Roman Catholic Church.

In her ground-breaking analysis of the formation of British modern identity (1992), Linda Colley demonstrated how Protestantism had ‘invented’ Great Britain and how the anti-Catholic component of a British (Protestant) identity was more than a simple theological or denominational issue. In fact, anti-Catholicism was also manifest in the political, social and cultural spheres. Since the Reformation, different types of anti-Catholicism had co-existed. Firstly, the official, legal and political form of anti-Catholicism, embodied in the Penal Laws (seventeenth century) which barred Catholics from political representation and penalised them on an economic and social level. Secondly, popular manifestations of anti-Catholicism could be found in the creation of militant Protestant societies and public demonstrations such as the celebrations of Guy Fawkes Day. These displays of anti-Catholicism went together with a third type, which lay in the social and cultural stereotyping of Catholics. They were represented as morally suspicious (e.g. the celibacy of priests), generally ignorant and uneducated, and easily manipulated by a tyrannical priesthood.

In the nineteenth century, religious tolerance towards Catholicism seemed to develop after Ireland’s entering the Union (1801) and the passing of the Roman Catholic Relief Act in 1829. Once the Catholics had been politically emancipated, a new era of acceptance ostensibly opened. Yet if tensions did resurface in the early 1850s with the restoration of the Catholic hierarchy in England, they were not encouraged by official authorities. As Yvonne Werner wrote in 2013, ‘the gradual dismantling of the legislation on compulsory religious adherence led to the politicisation of religious issues’. Consequently, new ultra-Protestant societies emerged across Britain to uphold the principles of the Reformation and keep a check on the ‘invasion’ of Britain by the papacy and its supporters. A fair number of these associations were quite vociferous up until the outbreak of World War II. In the later part of the twentieth century, increasing secularization led to new forms of Anti-Catholicism – as seen with 2010 Papal visit quoted earlier, and in more recent years, it would seem that the hard-core of the anti-Catholic movement (in Britain rather than in Northern Ireland) has certainly been emanating from humanist and secularist circles.

This symposium, bringing together French and British scholars, aims at exploring different facets of anti-Catholic doctrine, literature and physical demonstrations. Contributions range from studies from the 16th century up to the contemporary period and covers various areas of the United Kingdom.

PROGRAMME

09.00 – Welcome and Registration

09.30-09.45 – Introduction by Claire Gheeraert-Graffeuille and Geraldine Vaughan

09.45-10.15 – Géraldine Vaughan (Université de Rouen), Anti-Catholicism and British Identities

Seventeenth-Century Perspectives on Anti-Catholicism

10.15-10.45 – Luc Borot (Université de Montpellier), Early Modern English Catholics v. Anti-Catholic policies: Cultural, Spiritual and Political Resistance in the 17th century

10.45-11.15 – Christopher Hamel (Université de Rouen), Beyond ‘the general consent of the principall Puritans and Jesuits against Kings’: Milton and Sidney’s Rationalist Plea for Resistance

11.15-11.30 – Questions & Answers

11.30-11.45 – Coffee Break

A French Perspective

11.45-12.15 – Keynote Address: Valentine Zuber (EPHE Paris), On the other side of the Channel: Anti-Protestantism in Belle Epoque France

***

12.20-14.00 – Lunch Break (Maison de l’Université)

***

Anti-Catholicism in Britain and Scotland in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries

14.00-14.30 – Pascal Dupuy (Université de Rouen), Anti-Catholicism and Caricature in Britain, 1740-1815

14.30-15.00 – Clotilde Prunier (Université Paris Ouest), Anti-Popery in Eighteenth-Century Scotland: A Scottish Catholic perspective

15.00-15.30 – Martin Mitchell (University of Strathclyde), Anti-Catholicism in Scotland in the Nineteenth Century

15.30-15.45 – Questions & Answers

15.45-16.00 – Break

Perspectives on Contemporary Britain and Northern Ireland

16.00-16.30 – Leah Robinson (University of Edinburgh), Anti-Catholicism and Sectarianism in the United Kingdom during the 21st Century

16.30-17.00 – Karine Bigand (Université d’Aix-Marseille), Anti-Catholicism and Loyalism in Post-Conflict Northern Ireland – Representing the Other

17.00-17.30 – Questions & Answers

Closing Remarks